Management Responsibility and Control in Pharmaceuticals

Management

responsibility is fundamentally no different in the pharmaceutical industry than

any other business. The quote “The

buck stops here” made famous by the sign on the former U.S. President

Harry S. Truman’s

desk applies to anyone who holds the top job in any industry. The top

job is where the ultimate accountability resides for the company strategies and

decisions to achieve the intended

outcomes of the enterprise. For pharmaceuticals, management is individually responsible for ensuring that systems to comply with current good manufacturing practice

(CGMP) regulations are effectively implemented in order to establish and maintain a state of control for drug manufacturing, holding, and

distribution.

CGMPs

and state of control are inextricably connected. Lack of control leading to a

Field Alert and Recall due to the

potential of product being materially affected will be cited as violations of CGMPs.

The converse is also true. A pattern

of CGMP violations observed during a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) inspection will

also be viewed as lack of control, whether or not the product is materially affected. Either way, the

associated product will be deemed adulterated within the meaning of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA).

The implication of the impact of CGMP noncompliance on the business

is not theoretical. There are ample examples in the pharmaceutical

industry where ineffective implementation of CGMP systems resulted in loss of control that materially affected

product quality, which, in turn, affected inventory

and patient supply. Establishing a Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS) that

effectively implements the CGMPs is

the means for maintaining a state of control—the fundamental intent of these regulations.

Management

does not assume positions of responsibility with the intent of neglecting CGMP compliance. However, management may not

enter the top position fully equipped to assume responsibility for CGMPs in a practical way. Management may delegate all CGMP matters

to the Quality Department and take a hands-off approach and rely on this function to bring matters

to its attention at their discretion. Such passivity leads to hearing

only the bad news when it is far

too late to contain and resolve the problem in the most cost-effective way with

least risk to public safety.

Likewise,

some Quality Departments may not be adequately equipped to bridge the space between top management and daily

operations with effective structures and processes that enable management to exercise its responsibility

for CGMP oversight. Too often, the default position is to rely upon the outcome of regulatory inspections. But as one might expect,

a good outcome can give a

false sense of security, and a poor outcome can be viewed as the exhaustive

list of problems. As in any area of

the business where risks must be managed, there is no better approach than

having an intentional management

system in place that provides actionable data to know internally where your daily

operation stands at any given moment.

This

chapter provides a model for structuring a practical and effective management

system to fulfill this expectation. But first, it is useful

to understand the background for the FDA requirement for management to exercise its responsibility for oversight and control.

THE REGULATORY BASIS FOR MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITY

Historically, the FDA has cited the Supreme

Court decisions of United States

v. Dotterweich (1943)1 and United

States v. Park (1975)2 as

FDCA legal cases

that establish that the manager

of a corpora- tion can be

prosecuted under the Federal FDCA, even if there is no affirmation of wrong

doing of the corporation manager individually.

In

the Dotterweich case, the jury found Dotterweich, the president and general

manager of a drug repackaging

company, guilty on two counts for shipping misbranded drugs in interstate com- merce, and a third for shipping an

adulterated drug. One dissenting judge of the Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision on the

grounds that only the corporation was the “person” subject to prosecution, thus protecting the president personally. But the Supreme

Court reversed the decision, thus holding Dotterweich individually

responsible, not just the manufacturer. Justice Frankfurter delivered the opinion of the Court,

“…under § 301 a corporation may commit an offense and all persons

who aid and abet its commission are equally guilty….”

In

the Park case, the chief executive officer was found guilty on all counts

involving food held in a building

accessible to rodents and being exposed to contamination by rodents, resulting

in the adulteration of the food within the meaning of the FDCA. Park’s defense

was that he had an organi- zational

structure responsible for certain functions to handle such matters. However,

evidence from inspections of multiple locations

indicated the same problems and inadequate system for which he had overall responsibility. Chief Justice

Burger delivered the opinion of the Court, “…by reason of his position in the corporation,

responsibility and authority either to prevent in the first instance, or promptly to correct, the violation

complained of, and that he failed to do so…the imposition of this duty, and the scope of the duty,

provide the measure

of culpability…”

More

recently, Public Law 112–144 (July 9, 2012) called the Food and Drug

Administration Safety and Innovation

Act (FDASIA) added to the definition of CGMP in the FDCA (Section 501, 21 USC 351) to explicitly include management oversight of manufacturing to ensure quality.

Section 711 of FDASIA states:

For

the purpose of paragraph (a)(2)(B), the term “current good manufacturing

practice” includes the implementation

of oversight and controls over the manufacturing of drugs to ensure quality,

including managing the risk of and

establishing the safety of raw materials, materials used in the manufacturing of drugs, and finished drug products.

The addition

of oversight and controls to the definition of CGMP has strengthened the FDA position

with specific language for management’s responsibility for oversight and control as a requirement in the Act. The question remains how to practically and operationally to perform this responsibility. The fol- lowing model describes essential elements of a CGMP Management System for oversight and control.

THE QUALITY

MANAGEMENT TRIAD MODEL

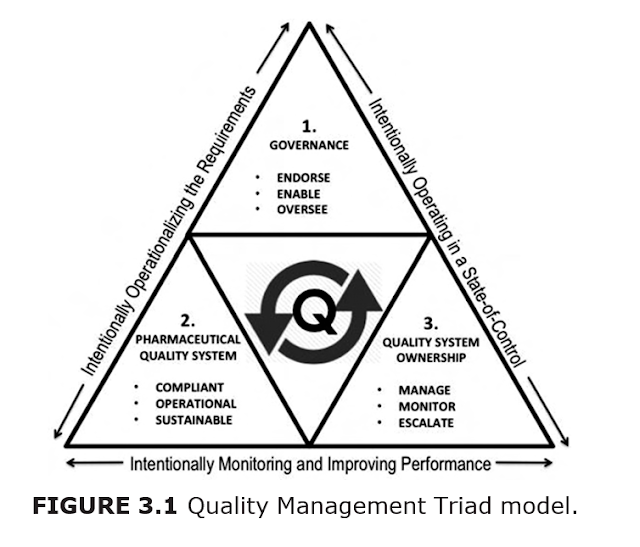

Three

elements form the framework of this model for designing and implementing

structures and processes that enable

management to exercise responsibility for oversight and control of CGMP compliance: Governance, the Pharmaceutical

Quality System, and Quality System Ownership.

These elements are interdependent, and the effectiveness of the model depends upon how well they are designed to work together. The

following sections discuss the key attributes of each element of the Quality

Management Triad model (Figure 3.1).

The Governance element

The governance body is comprised of the top leadership where the ultimate direction is given and decisions are made with respect to aligning resources, including those associated with CGMP compliance. Governance is the standard-bearer for what it endorses, enables, and oversees. To the watching organization, what management says, funds, and pays attention to, are the visible expres- sions of their values and the cultural setting for CGMP compliance.

Endorse

The governance body endorses a Quality Policy that declares the importance of CGMP compliance to the business by ensuring a continuous of supply of quality product to its patients. This policy provides the foundation for creating a set of Quality Standards that interprets and applies the CGMP regulations and current industry practice to its operations. Quality Standards are cross-functionally endorsed to demonstrate agreement with the minimum, irreducible requirements. Although Quality

Standards

establish the “What,” there is latitude for designing processes for “How”

requirements are met. Thus, CGMP

processes are opportune targets for continuous improvement. The “How” described in standard operating procedures

(SOP) is open to creative approaches for designing processes as efficiently as possible that also comply with the Quality Standards, and thus CGMP.

Enable

The

governance body enables CGMP compliance by providing the organization structure

and resources to implement and support processes

described in SOPs. While it is reasonable for manage- ment to question

whether a process

is designed as efficiently as possible, it is not reasonable to with- hold resources that affect the ability to

comply with Quality Standard requirements. Governance also establishes and partners with an independent Quality Unit

that has the product knowledge, technical

experience, and CGMP background to perform its unique regulatory

responsibilities. The Quality Unit

has the responsibility to objectively measure and report on the effectiveness

of the PQS, and management has the responsibility for oversight and control.

Oversee

The

governance body establishes the Quality Management Review (QMR) process to

oversee the ongoing performance of

the PQS and to give visibility to problems and risks as a means of under- standing the state of control. The QMR

process is a data-driven and action-oriented process to ensure that unacceptable risks and trends

are quickly identified and verifiably resolved.

The Quality Unit is best positioned to administer

the QMR process to ensure objective reporting, proper risk assessment, and verification that the intended

results of QMR decisions have been achieved.

Normal business processes,

such as planning and budget cycles, and operational goals and performance objectives, serve also to prioritize and focus company

attention where significant change or effort is necessary to improve CGMP compliance.

The

PharmaceuTical

QualiTy SySTem elemenT

The PQS is the interpretation and application of CGMP regulations to the operation. It is an integrated library of documents of increasing specificity from the Quality Policy and Quality Standards down to the SOP, and other executable work instructions. Like a balanced outline, the PQS has an overall structure with each topic taking its position as part of an intentional architecture. SOPs must be fit-for-purpose and remain relevant within a dynamic operational environment. Thus, the PQS is a living system that reflects the requirements, but it also is operational and sustainable the moment its documents become effective.

Compliant

Procedures and the records created by following procedures provide the legal history that affirms that the work was performed in compliance with requirements and that the expected results were obtained. There is no work related to manufacturing, holding, or distributing of drug product that is not described in an approved,

written procedure. There is a traceable path from the results entered

onto a record up through procedures and directly to standards and policies. It cannot be underestimated the importance to CGMP compliance of having clearly written procedures that logically describe the process steps, the persons who perform them, where results are recorded, and who reviews and interprets. Writing simply and clearly, along

with communication and training are special skills

required to establish effective procedures so that CGMP requirements are faithfully translated to those doing the work.

Operational

The

PQS is intended to work in the actual operation as soon as a procedure is

approved and implemented through training.

Process flow diagrams

are a useful tool in the hands of the user groups

to visualize the real-world steps of a process. They facilitate

discovery of the supplier of inputs, customers of outputs, and dependent linkages

to other processes that may need to be developed

or aligned for the overall process

to be effective. When and who makes decisions, as well as the conditions or situations in which the

Quality Unit is notified are also part of SOP content for the daily operation. For the PQS to be operational,

the user groups must actively participate to identify the obstacles

to getting work accomplished and having meaningful procedures.

Sustainable

The PQS must be sustainable by providing a supporting organization structure, adequate number of

skilled personnel, and an operating budget that are balanced with the demands

on the system. Significant operational changes such as acquisitions, facility

repurposing, production volume,

port- folio complexity, and

workforce levels invariably impact the effectiveness of PQS and present a compliance risk if not anticipated and

addressed. Performance metrics are the primary tools to continually monitor the performance of the PQS and to provide

the operational capability to self- detect

and self-correct problems. This capability is essential since continual

performance feedback is fundamental for sustaining performance and operating

in a state of control.

The Quality System

ownership element

The

PQS lives in a dynamic business and regulatory environment. Thus, the PQS must

be continually reevaluated to ensure its purpose is served. The Head of Quality

has functional responsibility for the

overall PQS, and management has the overall responsibility for oversight and

control. But knowledgeable and

skilled Quality System Owners (QSO) at the operational level are needed to take responsibility for ensuring that

their respective processes and procedures are continuously relevant, compliant, and integrated. Each

QSO has the responsibility for managing their part of the PQS,

monitoring performance, and escalating significant issues to management.

Manage

The

QSO is responsible for the resilience of their respective parts of the PQS

amidst the business changes around

them. The QSO has the knowledge and skills to ensure that his/her processes continue

to meet compliance requirements, are relevant to the operation,

fit-for-purpose, and perform effectively

and efficiently. This requires being up to date with CGMP regulations and

developing industry awareness

to remain current

with industry best practices. The QSO is the champion

for their respective processes and leads the

adoption of significant changes, as well as ongoing continuous improvement. The QSO is the subject-matter-expert and the face of their respective PQS processes.

Monitor

Data-driven information in the hands of a responsible and empowered QSO is essential

to the ongoing management of the system and maintaining a state of

control. Each QSO has carefully selected metrics

that provide ongoing and objective feedback about their respective part of the

PQS. There may be key performance

metrics adopted by the company or a site operation. There may also be popular ideas about metrics and what they

should or should not be. There may even be rules of thumb to limit the number of key performance metrics.

However, these should

not be confused with whatever performance metrics are personally

needed by each QSO to have the data necessary to take responsibility for the daily management and problem

detection. In the end, the QSO must be able

to answer two questions at any moment: How well is the system operating? What

problems or potential problems

is the system detecting? The QSO is in the best position

to decide on the performance metrics for the

systems for which they are responsible.

Escalate

The QSO must have directed a path to management to escalate problems

or potential problems

that represent unacceptable or unmanageable risk to the patient, the business, or CGMP compliance. The Quality Management

Review is the regularly occurring

forum where QSOs have the opportunity

to report on the state of their system. But there are instances where the degree of risk must permit

a direct and unfiltered alert to management. Some problems or potential

problems rise to the level where

either the cost of the permanent solution or the cross-functional impact

requires making the case directly and expeditiously to higher levels of management.

The role of Quality

Everyone

owns “CGMP compliance” much like everyone owns safety. Everyone has personal responsibility for having general CGMP

knowledge and awareness, and also having and following specific procedures relevant to their areas of responsibility.

However, the Quality Unit ensures that a strategy, such as this Quality Management Triad model, is in place

procedurally, in use behavior- ally,

and has the capability to objectively measure and report on the state of

control.

CONCLUSION

Management

has the legal responsibility for implementing the CGMP regulations and

overseeing and ensuring the

operational state of control. To operate in a state of control does not mean

perfection. It does mean, however, the capability of a firm to self-detect and

self-correct potential problems. And whenever a problem does emerge, the firm

is capable of taking action to understand the

underlying causes the problem or unacceptable trend, and make decisions

that favorably effect the trend, or that prevent

recurrence of the problem. The model described here provides the framework for developing and implementing a

practical and integrated system for management to have the means to exercise

responsibility and have data-driven knowledge of the state

of control.

REFERENCES

1.

United States v. Dotterweich, 320 U.S. 277 (1943)

2. United States

v. Park, 421 U.S. 658 (1975)

SUGGESTED READINGS

• J. Snyder, “Management Oversight of the Pharmaceutical Quality System: Obstacles and Opportunities.” Journal of GXP Compliance 17 (2), 2013, available at: http://www.ivtnetwork. com/management-oversight.

• J. Snyder, “Management Responsibility for the Quality System: A Practical Understanding for the CEO in FDA-Regulated Industries.” Journal of cGMP Compliance 3 (3), 55–59, 1999.

• J. Snyder, “Good Manufacturing Practices: Steps to Improve Quality,” invited author for chapter in Pharmaceutical Sciences Encyclopedia: Drug Discovery, Development, and Manufacturing. Ed. Shayne Gad. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 2010, Published online doi:10.1002/9780470571224.pse406.

J. Snyder, “Mindful Compliance: Where Knowledge and Regulations Meet.” BioPharm International Supplement, Guide to Good Manufacturing Practices, 26–34, 2004.

Reference: Good Manufacturing Practices for Pharmaceuticals (2020)

.webp)